By Colonel Mark C. Vlahos, USAF-Retired

I want to introduce a fellow researcher, author and good friend Mark Vlahos. He has kindly written a guest article for Forgotten Archives of History. At the end of the article you can find more information about Mark and his other work. Enjoy!

Since so much literature is already written on troop carrier, airborne, and glider operations in the European Theater of Operations (ETO), I focus my area of study on WWII troop carrier and glider operations in the Mediterranean Theater of Operations (MTO), including the secret war in the Balkans. United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) C-47s and CG-4A gliders were used extensively not only in the invasion of Sicily and Italy, and during the invasion of Greece, but also supported British SOE and American SOS operatives in former Yugoslavia.

One mission continues to stand out and intrigue me – the disastrous 1st Air Landing Brigade Ladbroke glider mission, which spear-headed Operation Husky – the invasion of Sicily. I know some readers are now thinking … This “Yank” must be crazy, bringing such an emotionally charged subject about a British glider mission. It’s understandable that many are of the opinion that it simply came down to the new, inexperienced American C-47 crews were afraid to fly into anti-aircraft fire and released the gliders too soon, so they landed in the water. However, this article will provide a fresh look at critical factors and offer up some new information, while challenging some previous assumptions. As far as the inexperienced American C-47 crews afraid to fly into anti-aircraft fire, I don’t buy it. We can never stop learning and that is why at this point in my life I work as a Historian, Author, and Speaker. Why is Ladbroke important? Because it was the first large-scale airborne mission attempted by the Allies in WWII. Also, this article will serve as a “teaser” for my fourth book that will be released later this year: American Glider Pilot’s in Sicily – The Untold Story of 26 Brave Americans in World War II by McFarland & Company, Inc. Publishers.

During Operation Husky planning, General Eisenhower’s staff apportioned the newly arrived USAAF 52nd Troop Carrier Wing (TCW) to the American sector with the task of dropping the American 82nd Airborne Division. [note: no glider tow mission was planned in the American sector.] The older and more experienced USAAF 51st TCW (comprised of the 60th, 62nd and 64th Troop Carrier Groups (TCGs) was apportioned to the British sector to support 1st Airborne Division missions.

The above chart summarizes major combat missions flown by the 51st TCW during the North African Campaign. Which brings up key point #1 – The 51st TCW was not untested in battle prior to Operation Husky. All three groups in the 51st TCW activated a year before Pearl Harbor and were some of the oldest in the Army Air Corps. In fact, most of the thirty-nine C-47s that flew the Operation Torch mission were fired upon by anti-aircraft guns upon reaching Algeria; three of the C-47s, loaded with U.S. paratroopers were forced or shot down and shot up pretty good by French fighter aircraft as well. Casualties for the 60th TCG on the Torch Mission were 2 killed, 7 wounded, the paratroopers they carried suffered 5 killed, 20 wounded.

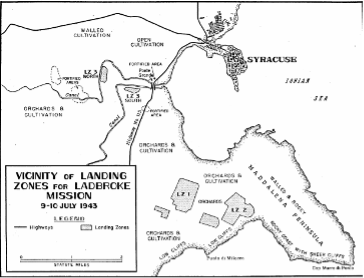

For D-day of Operation Husky, the 60th, 62nd TCGs and 38 Wing RAF were tasked to tow 144 gliders transporting the British 1st Air-landing Brigade. Of the 144 gliders, 136 were American Wacos and 8 were British Horsas. The 144 tug ships consisted of 109 C-47/C-53 from the 51st TCW and 28 Albermarle and 7 Halifax bombers from RAF 38 Wing. The mission was code-named Ladbroke; to secure the vital Ponte Grande Bridge on the main highway over a canal southwest of the city of Syracuse on Sicily. Another 250 American C-47s were committed to dropping the 82nd Airborne Division, with 63 more held in reserve. [note: Two follow on missions’ code-named Glutton and Fustian were also planned for the British sector. Glutton was cancelled, but Fustian, a combination paratroop and glider tow mission flew on the night of July 13-14, 1943.]

Lieutenant Colonel George Chatterton, Commander of British glider pilots was well aware of the risks involved with the Ladbroke Mission. It is well-known that Major General “Hoppy” Hopkinson, Commander, 1st Airborne Division threatened to relieve Chatterton of command when Chatterton voiced his concerns. [note: The author is totally impressed with the leadership displayed by George Chatterton both before and after the Ladbroke Mission.] Since not nearly enough British Horsa gliders could be ferried to North Africa, the duty of flying the majority of 1st Air Landing Brigade into combat fell upon the smaller American CG-4A Waco glider. The glider British pilots had zero flying time on the CG-4A, and to make matters worse, General Montgomery directed a night time landing for the gliders, over some very unforgiving terrain. At this time, night glider assaults were not part of British Airborne Doctrine; British glider pilots had zero night flying experience. In contrast, to earn their wings, American glider pilots trained in both day and night operations and landings. With time running out, there was a lot of pressure to not only assemble enough Waco gliders, but also train the British glider pilots to fly them. When it was all said and done, each British glider pilot amassed about 4.5 hours of flying time, with 1.2 hours at night on Wacos.[1]

Now for key point #2 of this article. The British were not happy with the size and capability of the Wacos as a replacement for the Horsa. Prior to Operation Husky, British Royal Engineers added three more wooden seats to the Waco’s, so a total of 16 paratroopers could be carried.[2] While not every glider carried 16 men, there are multiple load manifests that document gliders with 16 men. With combat gear, an additional 3 more paratroopers and the wood seats added between 700 - 1000 more pounds to the payload. The Waco was designed to carry about 4,000 pounds into combat. Since British glider load planning was based around the platoon, my assumption is that these three extra seats were added to create half a platoon load – for ease of load planning (basically cutting a Horsa platoon load in half).

However, a lot more risk was built into the Ladbroke plan. British planners were concerned the American C-47s had no armor or self-sealing gasoline tanks. Since the C-47s were needed for follow-on paradrop missions, British Ladbroke planners directed to keep the C-47 tug and CG-4A glider combinations out of anti-aircraft range. This is why the planned release point (directed on British Field Order #15) was chosen to be 3,000 yards (= 1.7 miles) offshore, over water, at an altitude of only 1400 feet at night. It is important to note that this drop location and altitude was based on calm winds. To make matters worse, the landing zones (LZs) were located on top of a 200-foot-high cliff with many rocks, stone walls, and ditches. One Waco LZ was an additional one mile inland from the shoreline.

Ladbroke – High Risk Mission

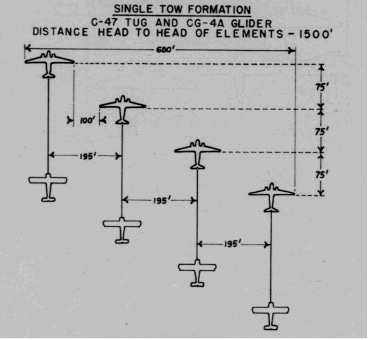

To fully understand What happened that night, a closer look at the formation the USAAF C-47s flew must be made. Worried that Axis radar on Sicily would detect the C-47 formation, Ladbroke planners directed the entire 400-mile flight to glider release to be made at an altitude of 200 feet above the water. This was a very tight and aggressive formation to fly, especially at night, towing a glider, and flying only 200 feet above the water.

The C-47 tug aircraft would then climb to an altitude of 1400-1800 feet to release the gliders in the release zone. Due to a shortage of navigators, only one navigator was assigned to each 4-ship element lead aircraft. The USAAF 4-ship single glider tow element had all aircraft in right-echelon and a little further back from the lead aircraft.

With less than 24 hours go before takeoff on the Ladbroke Mission, Lt. Col Chatterton approached Brigadier General Dunn, the 51st TCW Commander and stated they were short 26 glider pilots to fly the two-planned glider missions and asked the Americans for help. Each American Troop Carrier Squadron was asked to provide 5 glider pilots to support the effort. In each squadron, the first five volunteers were taken; the American glider pilots had no idea what they were volunteering for and did not know the next day they would be taking off as part of the British 1st Airborne Division to spearhead the invasion of Sicily.

The British field orders for the American tug crews in Ladbroke were explicit. Do not go over land, Do not get into flak (the concern of no self-sealing gas tanks), release gliders 3000 yards from shore and, the most radical order was if the Glider pilot did not release on their signal, the tugs were to release them. The unwritten guidance was “don’t come home towing a glider.” This was totally unheard of by American glider pilot flight training standards and the American glider pilots could not believe what they were bring told. The Operations Order dictated release altitude for the Waco LZs was 1400 and 1800 feet in altitude, and 4,000 feet for the Horsas.

No plan survives first contact with the enemy and at takeoff time the enemy was the weather. A gale force wind of 35 – 45 knots out of the west/northwest was blowing. More than one American C-47 crew member was concerned with the briefed low glider release altitudes. Second Lieutenant Paul Gale, a navigator in the 51st Troop Carrier Squadron stated: “The winds were gale force winds, up to forty-five knots. We had not been given any change of the release co-ordinates. When you went to the briefings, they told you where you were going, what routes they expected you to fly and where they expected you to release these gliders: latitude, longitude and altitude. We received no information of a change of these co-ordinates which had to be changed because the co-ordinates that we had were all for five or ten knot winds or calm weather. Key point #3; At the briefings, the Americans suggested the release altitude be raised an additional 2,000 feet for the Wacos due to the wind, but the British declined to do this. In all fairness, there was no telephone connection between the six takeoff airfields and since radio silence was directed, there was no way to communicate a change in glider release altitude this late in the game. Sadly, if the Waco gliders were released 2,000 feet higher, many more would have reached shore.

With no instrumentation to assist and not trained to judge distance offshore at night – the Troop Carrier pilots did the best they could– but still, lead Navigator Richard H. Kraemer got the front part of the formation within a quarter-mile of the release point. Half (50%) of the Wacos in the first three, 4-ship elements made landfall. It is what happened after this that things went bad.

A combination of four things caused the ensuing disaster: the high velocity of the wind, overweight gliders, the briefed release altitude (too low) and the actual 4-ship element flown by the Americans – it was not C-47 crews running from anti-aircraft fire as some sensationalize. Only nine British reports mentioned tugs taking evasive action and only a few tied this evasive action to anti-aircraft fire. Also, many tugs are documented as making a second and even a third run-in after missing the release point – this proves they were trying their best to execute the mission. The wind became almost a direct cross wind to the tugs from the direction of shore; and a direct head wind to the gliders once released. Accounts vary, on the wind speed, but probably averaged around 35 mph.

When flying an echelon right formation, the only way to create safe space from other aircraft is to move right, further away from shore and the release point. Number 3 and 4 kept getting pushed right to maintain safe distance from 1 and 2. This caused many gliders to be released more than 3,000 yards offshore.

As the lead elements slowed down and climbed to release altitude, the following elements in the formation began to stack up and the formation became compressed. As the formation became compressed, elements had to go further right (and further offshore) to keep from flying into those in front of them. To make matters worse; those aircraft that flew past the release zone without releasing attempted to circle back and fly back into the incoming flow – this was the worst thing they could have done. This caused the evasive action, documented in many reports. The back half of the formation had many more re-attack attempts, this only messed up the formation more and the results proved it. It’s a miracle that no mid-air collisions occurred. Many pilots reported that aircraft and gliders were all over the sky. Trying to release gliders in a 4-ship element just made things worse for the glider pilots.

The lead 60th TCG in the front half of the formation was more accurate (25 gliders reached land/23 sea/3 returned) than the back half 62nd TCG (only 13 reached land/36 sea/2 returned). Sadly, the majority of the British Border Regiment was in the back half of the formation and suffered nearly 200 casualties. The tug pilots under orders to release gliders made things worse– sadly many were too far offshore (the results of the back half of the formation support this). Again, if the release altitude was raised another 2000 feet, another 20 – 25 gliders may have reached shore.

After the disastrous results on the Ladbroke Mission, the British glider pilots refused to be towed by the American Troop Carriers. Ironically, many of the directives that handcuffed the American troop carrier pilots on Ladbroke, were removed in the field order for the follow-on Fustian Mission. British Tug aircraft flew directly over the landing zones, glider pilots-initiated release, and the landing zones were marked. Despite all that went wrong after Operation Husky – on both the American drop of the 82nd Airborne and the two British missions, Lieutenant Colonel Chatterton and Brigadier General Ray Dunn were determined to push lessons learned and convince General Eisenhower that glider operations could be successfully accomplished. The bottom line was the Force involved was barely trained for the mission tasking at hand and many lessons learned, sadly in blood where taken to task – which paid huge dividends just a year later in France, Holland, and Germany in the European Theater of Operations and Greece and Yugoslavia in the Mediterranean Theater of Operations.

Colonel Mark “Plug” Vlahos retired from the United States Air Force in 2011. During his 29-year career, he served in a wide range of operational flying and staff assignments including command of a C-130 squadron in combat and Vice Wing Commander of the 314th Airlift Wing at Little Rock Air Force Base, Arkansas. Mark attended Virginia Polytechnic Institute & State University and holds master’s degrees from Webster University and the Industrial College of the Armed Forces. He is a member of The Order of Daedalians, the Troop Carrier/Tactical Airlift Association, the Air Force Historical Foundation, the British Glider Pilot Regiment Society, and the Leon B. Spencer Research Team of the National World War II Glider Pilots Association. An expert on World War II C-47 and glider operations, Mark is the author of numerous books and articles. He resides in New Braunfels, Texas. You can see a listing of his books at https://markcvlahos.com

[1] John C. Warren, Airborne Missions in the Mediterranean, 1942 – 1945, p.35.

[2] Source: 51st TCW A-3 Diary, 19 June 43’ confirmed also by HQ NAAFTCC Report of Operations and Activities including the Sicilian Campaign 18 May – 31 July 1943.